Gotham (typeface) – Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

Gotham is a family of widely used geometric sans-serif digital typefaces designed by American type designer Tobias Frere-Jones in 2000. Gotham’s letterforms are inspired by a form of architectural signage that achieved popularity in the mid-twentieth century, and are especially popular throughout New York City.[1]

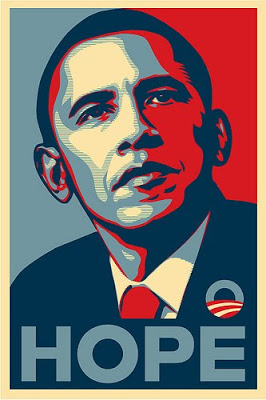

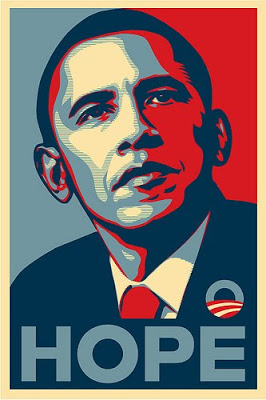

Since creation, Gotham has been highly visible due to its appearance in many notable places, including a large amount of campaign material created for Barack Obama’s 2008 presidential campaign, as well as the cornerstone of the One World Trade Center, the tower to be built on the site of the former World Trade Center in New York. It is also the current font to be used in title cards for film trailers in the US.

[…]

The Gotham typeface was initially commissioned by GQ magazine, whose editors wanted to display a sans-serif with a “geometric structure” that would look “masculine, new, and fresh” for their magazine. GQ agreed that they needed something “that was going to be very fresh and very established to have a sort of credible voice to it,” according to Jonathan Hoefler.[2]

Frere-Jones’ inspiration for the typeface came from time spent walking block-by-block through Manhattan with a camera to find source material,[3] and he based the font on the lettering seen in older buildings, especially the sign on the Eighth Avenue facade of the Port Authority Bus Terminal. “I suppose there’s a hidden personal agenda in the design,” Frere-Jones said, “to preserve those old pieces of New York that could be wiped out before they’re appreciated. Having grown up here, I was always fond of the ‘old’ New York and its lettering.”[3]

The lettering that inspired this typeface originated from the style of 1920s era sans-serifs like Futura, where “Type, like architecture, like the organization of society itself, was to be reduced to its bare, efficient essentials, rid of undesirable, local or ethnic elements.” This theme was found frequently in Depression-era type in both North America and Europe, particularly Germany.[4] This simplification of type is characterized by Frere-Jones as “not the kind of letter a type designer would make. It’s the kind of letter an engineer would make. It was born outside the type design in some other world and has a very distinct flavor from that.”[2]

Reviews of Gotham focus on its identity as something both American and specific to New York City. According to David Dunlap of The New York Times, Gotham “deliberately evokes the blocky no-nonsense, unselfconscious architectural lettering that dominated the [New York] streetscape from the 1930s through the 1960s.”[5] Andrew Romano of Newsweek concurs. “Unlike other sans serif typefaces, it’s not German, it’s not French, it’s not Swiss,” he said. “It’s very American.”[6]

According to Frere-Jones, Gotham wouldn’t have happened without the GQ commission. “The humanist and the geometric … had already been thoroughly staked out and developed by past designers. I didn’t think anything new could have been found there, but luckily for me (and the client), I was mistaken.”[3]

[…]

Early materials for the Obama campaign used the serif Perpetua. Later, however, upon hiring John Slabyk, and Scott Thomas, the campaign made the change to Gotham, and the font was used on numerous signs and posters for the campaign.[7]

The International Herald Tribune praised the choice for its “potent, if unspoken, combination of contemporary sophistication (a nod to his suits) with nostalgia for America’s past and a sense of duty.”[8] John Berry, an author of books on typography, agreed: “It’s funny to see it used in a political campaign because on the one hand it’s almost too ordinary yet that’s the point. It has the sense of trustworthiness because you’ve seen it everywhere.”[9] Graphic designer Brian Collins noted that Gotham was the “linchpin” to Obama’s entire campaign imagery.[10]

Observers of the primary and general elections compared Obama’s design choices favorably to those made by his opponents. In her campaign, Hillary Clinton used New Baskerville, a serif used by book publishers, law firms, and universities, while John McCain used Optima, the same font used for the Vietnam Veterans Memorial.[8][11]

[…]

On April 4, 2011, Hoefler and Frere-Jones announced that they had created a new custom version of Gotham with serifs for the use of President Barack Obama’s 2012 campaign. In announcing the news they wrote: “Can We Add Serifs to Gotham? For the President of The United States? Yes We Can.[19] Following the closure of the 2012 US presidential elections, this serif version of Gotham has not yet been released publicly.